I grew up hating my self. There was not anything about me that someone did not tell me I need to do differently. I was a Tommy Boy, over weight, struggled with reading and school (diagnosed with dyslexia in the 3rd grade). I tried to change who I was to fit the many influences. But with a select few friends I was able to just be me. I will forever be grateful to Kim and her family who never tried to change anything. They just loved me.

Unfortunately, I fell in love with someone who I thought loved me too, but as soon as we were married, he wanted me to change everything about me. His abuse started off with verbal abuse which then turned sexual and then physical.

Amazingly, Joseph saw me. When he told me that he could see himself married to me, I tried to tell him how broken I was. I did not believe I was loveable and I did not love myself. I was ashamed of who I was and what I have been through.

Joseph and I married in 1999, we started a family. He saw through my trauma and triggers and he encouraged me to get help. He was my soft place to fall when I was not strong enough to stand.

While working for Two Little Hands Products they offered the employees training that was a self-discovery seminar. Joseph also went through the seminar and that is where everything started changing. Not changing because someone was telling me I needed to be different, but because I started learning that there was nothing wrong with me. My past was just what happened not who I was.

A friend I made during the seminar gave me the book “Remembering Wholeness” by Carol Tuttle. Joseph, got it for me on Audible so I could listen and follow along. I learned how to reconnect to my spiritual roots, to stop identifying myself through the eyes of others, my past, my fears and my failures. I learned that my thoughts shape my reality. I started following her work, I learned EFT and started learning more about other energy-clearing techniques.

For the first time I started love learning. The more I listened while following with books the easier reading became. I still us that technique as I have much better understanding and recall when I listen and follow along. I also started asking who God saw me as and what he needed me to become.

Along this journey, I started using essential oils and in October of 2013 I became a doTERRA Wellness Advocate. At my first doTERRA Convention, I felt inspired to start blogging about my experiences with mental health and abuse. Joseph was my biggest supported as I started sharing. But not everyone in my life where as supportive. In 2014 I became Certified as an AromaDance Instructor and Certified in AromaTouch Technique. In January of 2018 I became Certified Essential Oil Coach. This allowed me to see that I could do hard things. I kept finding things that interested me and that helped me learn more about myself.

Over 10 years ago Mary Lambert – Secrets became my theme song. I no longer care if people know about my past and my insecurities.

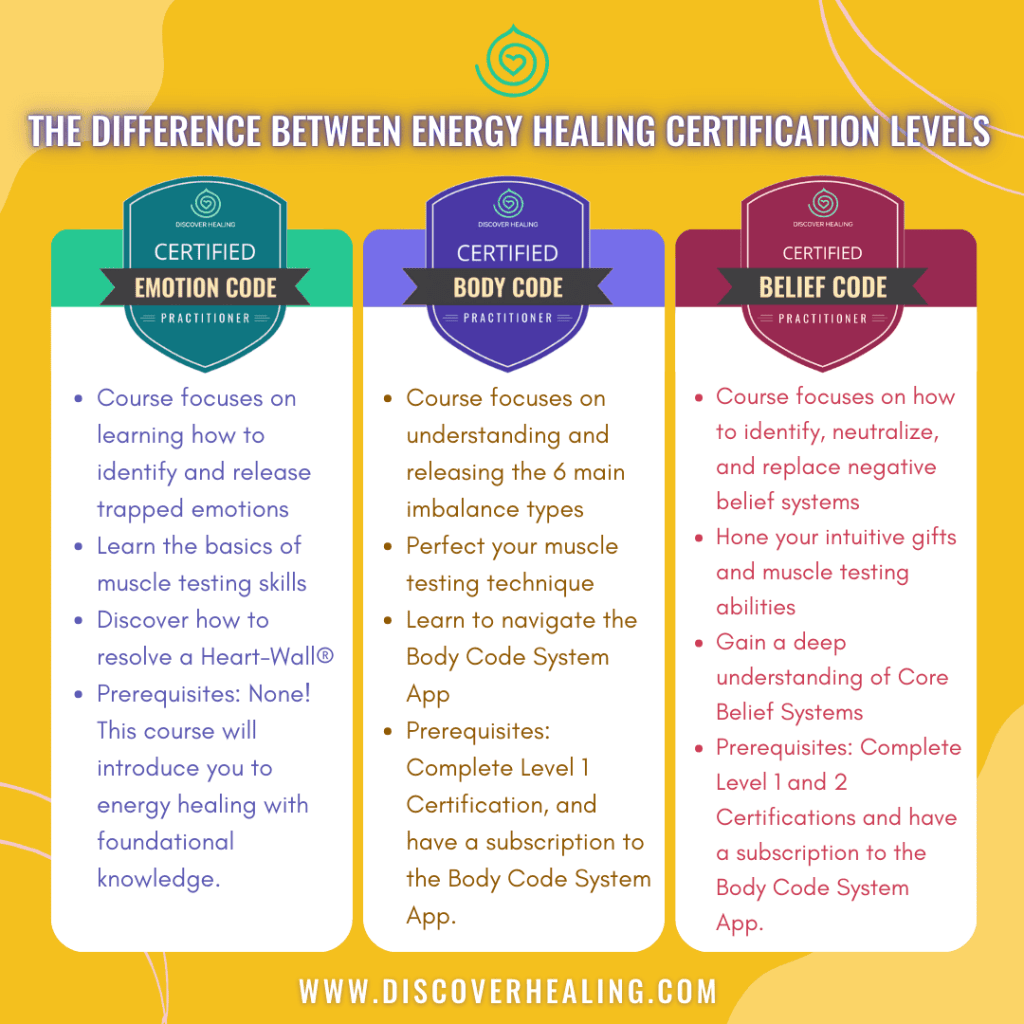

In 2019, Ronai Brumett introduced me to the work of Bradley Nelson and the Emotion Code. In May of 2020 I completed my Emotion Code Practitioner Certification. In July of 2021 I completed my Body Code Certification.

In January of 2022, I started something I never thought I would do. I want back to school to get my degree. Although I loved learning college is hard. While doing college in n July of 2024 I completed my Belief Code Certification. In October 2025 I completed my Associate of Applied Science in Family and Human Services from Brigham Young University Idaho.

Along the way I started learning to love myself. I am not perfect at it. I spent over 40 years hating a lot of things about myself. As I have used the skills I have learned with Essential Oils, Emotion Code, Body Code, Belief Code, AromaDance, Mindful Movement, and through my college education I have release things that no longer serve me and I started loving pieces of myself. I am a work in process and I am grateful for who I am.

For one of my class projects I focused on selfcare without the guilt. This was not easy, but over the 4 weeks I started seeing the benefits of taking care of myself first. I discovered that self-care is not selfish—it is foundational. It is the fuel that supports your mind, body, and spirit, allowing you to show up fully in your life rather than running on empty. When you honor your need for rest, nourishment, connection, and regulation, you are not taking away from others—you are strengthening your capacity to love, serve, create, and heal. Self-care is an act of wisdom, stewardship, and self-respect.

I have created a journal to help you do what I did for myself.

During the process I have found what selfcare method support me for different situation. Dance is one of my best tool. Along the way I came across two more theme song for my journey. I am grateful for the Positivity Able Heart is putting out into the world. I think we are kindred spirits. Give them a listen.

As I began practicing self-care intentionally—without guilt, without justification, and without waiting until everything else was done—I noticed something profound: my capacity to cope, connect, and heal expanded. What started as a deeply personal journey slowly became something I wanted to understand more fully. I didn’t just want to know that self-care felt helpful—I wanted to know whether it was supported, especially for those of us who have lived with trauma, burnout, or years of believing our needs didn’t matter.

What I discovered was validating and freeing: modern, peer-reviewed research consistently shows that self-care is not selfish, indulgent, or optional—it is foundational. The very practices we are often taught to feel guilty for—rest, emotional regulation, boundaries, reflection, and nourishment—are the same practices shown to protect mental health, reduce stress and burnout, and support long-term resilience. Science now confirms what many of us learn the hard way: caring for ourselves is not taking away from others; it is what allows us to show up fully, sustainably, and authentically.

The research below helps remove guilt from self-care by reframing it as a necessary, evidence-based component of well-being. It supports what this journal is designed to do—help you honor your needs without shame, choose care without apology, and understand that tending to your mind, body, and spirit is not a failure of strength, but an expression of it.

Self-care practices—intentional actions individuals take to maintain or improve their physical, mental, and emotional health—have been consistently linked to improved psychological well-being and reduced stress. Research indicates that engaging regularly in activities such as mindfulness, physical rest, and holistic health behaviors strengthens resilience and mitigates the effects of stress, burnout, and psychological distress across diverse populations (Tushe, 2025). For example, studies show that structured self-care activities such as mindfulness training can significantly decrease stress and burnout while enhancing psychological resilience in students and professionals alike, suggesting that these practices function as protective factors in the face of ongoing demands rather than indulgences (Chen et al., 2025; Kwon, 2023). This evidence underscores self-care as a proactive lifestyle component that supports long-term adaptive functioning rather than a luxury reserved for the “less busy.”

Empirical research further demonstrates that self-care supports emotional regulation and mental well-being by fostering mindful awareness and self-compassion, which are associated with better stress management and interpersonal functioning. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses find that regular engagement in mindful self-care practices correlates with positive mental health outcomes, including increased self-acceptance, emotional balance, and reduced burnout symptoms in various helping professions (Monroe et al., 2021; moment). These outcomes show that self-care enables individuals to remain present, manage daily stressors effectively, and engage with life more fully—not because they are indulgent, but because they build essential psychological capacities that sustain performance, relationships, and overall health.

Importantly, research also highlights that self-care is not equally easy to adopt in conditions of elevated stress, which can paradoxically make people feel guilt or pressure when they struggle to practice it. Studies examining self-care behaviors during stressful situations such as the COVID-19 pandemic show that higher perceived stress can negatively impact the likelihood of engaging in self-care, which in turn weakens its beneficial effects on well-being (BMJ Open, 2021). This finding highlights a common challenge: guilt or internal resistance toward self-care may arise when it feels difficult, but the evidence clearly points to self-care as a key mediator that improves psychological health when regularly enacted. Rather than being selfish, self-care has a vital role in preserving wellness across life’s demands.

Loving Me

by LeeAnn Mason

I am removing the labels and stories that defined me

I am healing the child I am setting them free

I have been broken I have been beaten but they’re not going to win

I am choosing to stand up to heal from within

I am safe to feel

I am safe to heal

I am am loving me

I release what no longer serves me

I receive all that God created me to be

I am choosing the unique strengths God gave me

I am choosing to love and heal to serve myself free

I have overcome the strife

I give gratitude to every part of my life

I no longer beg I no longer fight

I claim my power, love and light

I am safe to feel

I am safe to heal

I release what no longer serves me.

I receive all god created me to be

I am am loving me

I set myself free

Created by LeeAnn Mason/Beyond Possibilities LLC with AI.

Reference List

Ayala, E. E., Winseman, J. S., & Johnsen, R. D. (2018). U.S. medical students who engage in self-care report less stress and higher quality of life. BMC Medical Education, 18, 189. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-018-1296-x

Chen, S., Qi, X., & colleagues. (2025). A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness: Effects on academic stress, academic burnout, and psychological resilience in university students. Frontiers in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1722669

Kwon, J. (2023). Self-care for nurses who care for others: The effectiveness of meditation as a self-care strategy. Religions, 14(1), 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14010090

Monroe, C., Loresto, F., Horton-Deutsch, S., Kleiner, C., Eron, K., Varney, R., & Grimm, S. (2021). The value of intentional self-care practices: The effects of mindfulness on improving job satisfaction, teamwork, and workplace environments. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 35(2), 189–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2020.10.003

BMJ Open. (2021). Relationship between self-care activities, stress and well-being during COVID-19 lockdown: A cross-cultural mediation model. BMJ Open, 11(12), e048469. https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/11/12/e048469

Tushe, M. (2025). The role of self-care practices in mental health and well-being: A comprehensive review. Journal of Nephrology & Endocrinology Research, SRC/JONE-148.